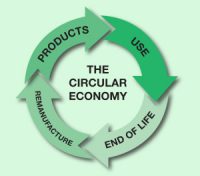

The idea that the circular economy will eat into existing sales, and two other myths, are contributing to a halt in the model’s acceptance among businesses.

The idea that the circular economy will eat into existing sales, and two other myths, are contributing to a halt in the model’s acceptance among businesses.

Martin Stuchtey, Director of the McKinsey Centre for Business & Environment, wrote an article for The Guardian debunking some of the common misconceptions about the circular economy.

The first myth he deals with is the idea that going circular will “cannibalise” current sales. He responds by drawing from the analogy of used cars, which only compete with new cars “if car companies let others make the next sale”, and so the aftermarket “can become an additional profit centre” for the manufacturer.

Another method for preventing re-engineered items from eating into the existing market is to aim them at places where the market has not yet penetrated, like Patagonia, which collects and sells used clothes and other items where its new ones are not available. He also cites the case of Renault, which has invested in car remanufacturing to re-use its parts and materials.

Stuchtey says that “this circular approach not only reduces resource consumption, but cuts H&M’s input costs”, while the McKinsey Centre has found that “as long as quality is maintained, refurbished systems can deliver substantially higher margins”. He further clarifies that it is good business thinking when “companies begin to think of what goes out their doors as the possible start of another business cycle”.

The second myth is that customers prefer new-builds, to which the writer retorts that while there are people who “want the newest thing” there is also an emerging sector of “individuals who favour service over ownership”, such as young people in Germany who are choosing to car-share rather than drive their own vehicle as previous generations have.

He continues with the assertion that “old versus new is a 20th century way of thinking anyway” and that high quality products can easily be made from “old stuff”, especially since consumers are most interested in the product being effective in getting the job done. The drill, which most households use for only a few minutes a year, could easily be provided as a service by being leased or leant under a circular model, rather than “as a product through purchase”.

Finally, he addresses the concept that the circular model is too complex to set up. Stutchey posits that while creating the model can be complicated, “capitalising on service models is a strategic imperative that goes way beyond the circular economy” and that the model can cultivate a close relationship between companies and consumers “that benefits both parties”.

He also sees potential in business-to-business transactions, such as lighting manufacturers who sell lamps and bulbs that are now moving into providing the light as well. The company then “has every incentive to provide light in the most efficient way” and has “a secure flow of returned devices” to recycle or reuse parts from.